Il corso di laurea in Fisica dell'Atmosfera e Meteorologia organizza l'attività di orientamento:

"Come osservare l’Atmosfera: metodi, strumenti, misure"

Quinto Congresso Scientifico di Orientamento alla Fisica dell’Atmosfera, Meteorologia e Climatologia nei locali del dipartimento di Fisica (V.le Berti Pichat 6/2, piano -1) a Bologna il giorno 2 marzo 2011.

Maggiori dettagli e la locandina del congresso sono consultabili sul sito di facoltà

http://corsi.unibo.it/Laurea/FisicaAtmosferaMeteorologia/Eventi/2011/02/quinto-congresso-fam.aspx

lunedì 21 febbraio 2011

mercoledì 16 febbraio 2011

Winter Cloud Streets, North Atlantic

What do you get when you mix below-freezing air temperatures, frigid northwest winds from Canada, and ocean temperatures hovering around 39 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit (4 to 5 degrees Celsius)? Paved highways of clouds across the skies of the North Atlantic.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite collected this natural-color view of New England, the Canadian Maritimes, and coastal waters at 10:25 a.m. U.S. Eastern Standard Time on January 24, 2011. Lines of clouds stretch from northwest to southeast over the North Atlantic, while the relatively cloudless skies over land afford a peek at the snow that blanketed the Northeast just a few days earlier.

Cloud streets form when cold air blows over warmer waters, while a warmer air layer—or temperature inversion—rests over top of both. The comparatively warm water of the ocean gives up heat and moisture to the cold air mass above, and columns of heated air—thermals—naturally rise through the atmosphere. As they hit the temperature inversion like a lid, the air rolls over like the circulation in a pot of boiling water. The water in the warm air cools and condenses into flat-bottomed, fluffy-topped cumulus clouds that line up parallel to the wind.

Though they are easy to explain in a broad sense, cloud streets have a lot of mysteries on the micro scale. A NASA-funded researcher from the University of Wisconsin recently observed an unusual pattern in cloud streets over the Great Lakes. Cloud droplets that should have picked up moisture from the atmosphere and grown in size were instead shrinking as they moved over Lake Superior. Read more in an interview at What on Earth?

1.

References

2. NASA Earth Observatory (2006, January 31). Cloud Streets in the Bering Sea. Accessed February 14, 2011.

3. NASA Earth Observatory (2005, November 29). Cloud Streets Pave Hudson Bay. Accessed February 14, 2011.

4. Weather Online (n.d.). Cloud streets. Accessed February 14, 2011.

NASA image by Jeff Schmaltz, MODIS Rapid Response Team, Goddard Space Flight Center. Caption by Michael Carlowicz.

Instrument:

Terra - MODIS

Nasa Earth Observatory del 15 febbraio 2011

mercoledì 9 febbraio 2011

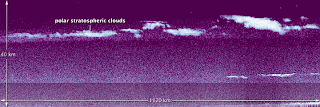

CALIPSO Spies Polar Stratospheric Clouds

NASA’s Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation (CALIPSO) satellite was in the right place at the right time earlier this month. On January 4, 2011, while flying over the east coast of Greenland, CALIPSO caught a top-down glimpse of an unusual atmospheric phenomenon—polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs), also known as nacreous clouds.

Clouds do not usually form in the stratosphere because of the dry conditions. But in the polar regions, often near mountain ranges, atmospheric gravity waves in the lower atmosphere (troposphere) can push just enough moisture into the high altitudes. The extremely low temperatures of the stratosphere condense ice and nitric acid into clouds that play an important role in depletion of stratospheric ozone.

The top image was assembled from data from CALIPSO’s Light Detection and Ranging instrument, or lidar, which sends pulses of laser light into Earth's atmosphere. The light bounces off particles in the air and reflects back to a receiver that can measure the distance to and thickness of the particle- and air masses below. The data was acquired between 4:30 and 4:44 Universal Time on January 4, 2011, as the satellite flew 1120 kilometers (695 miles) from north to south over the Greenland Sea and Denmark Strait, as depicted in the map above.

CALIPSO has observed stratospheric clouds before, but never one this high, says Mike Pitts, an atmospheric scientist at NASA's Langley Research Center. This cloud reached an altitude of more than 30 kilometers (19 miles).

The cloud was the result of mountain waves in the atmosphere, which form when stable air masses pass over mountains or high ice sheets, providing vertical lift. Pitts said such stratospheric ice clouds are rare because they only form when the jet stream in the Arctic is properly aligned with the edge of the polar vortex, a large air pressure system over the poles. The circulating air in the vortex needs to align with the jet stream to create enough vertical motion and propagate the waves to the upper atmosphere. The January 4 cloud was formed when those winds aligned and sent an air mass up over the high ice sheet and mountains of Greenland.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using CALIPSO data provided by the Langley Atmospheric Science Data Center, with meteorological analyses by Andreas Dörnbrack, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, DLR Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany. Caption by Kristyn Ecochard and Michael Carlowicz.

Instrument:

CALIPSO - CALIOP

Nasa Earth Observatory del 9 febbraio 2011

Iscriviti a:

Post (Atom)